Source: Eparchy of Newton

Beginning with chapter 8, the Acts of the Apostles tells how the message of Christ’s resurrection spread from Jerusalem to surrounding areas. We see the deacon Philip evangelizing and baptizing in Samaria, where he is joined by the apostles Peter and John. Philip then travels westward, as far as Caesarea, the Roman provincial capital. In chapter 9 we learn that there are believers in Damascus whom Saul goes to capture. Peter also travels, healing Aeneas in Lydda (Lod) and raising Dorcas in Joppa, both today suburbs of Tel Aviv. He then goes some 75 miles up the coast to Caesarea where he ministers in the house of Cornelius.

As often happens, persecution in one place led to the spread of the Gospel in another, Chapter 11 tells how persecution scattered the disciples even further: “as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch” (Acts 11:19), The Gospel had now gone over 300 miles in its journey around the world.

Contents [hide]

1 Antioch the Great

2 1st -3rd Centuries – Martyrs and Ascetics

3 4th-6th Centuries – Councils and Disputes

4 7th -13th Centuries – Occupation & Exile

ANTIOCH THE GREAT

Called “the Great” to distinguish it from cities in other provinces called Antioch, the city was founded in the 4th century bc by Seleucus I Nicator as a “court city” of his Seleucid Empire. In 64 bc Syria became part of the Roman Empire. Antioch eventually rivaled Alexandria as the chief city of the Middle East and played a particularly strong role in the Roman Empire.

Syria had a sizeable contingent of Jews who had full status as citizens. It is likely that the believers fleeing Jerusalem established themselves in the midst of this prosperous colony. We are told in Acts that these believers preached the Gospel, “only among Jews. Some of them, however, men from Cyprus and Cyrene, went to Antioch and began to speak to Greeks also, telling them the good news about the Lord Jesus. The Lord’s hand was with them, and a great number of people believed and turned to the Lord” (Acts 11:19-21). These first Gentile converts were called “Christians,” probably not a complement at first.

The new community was instructed by Barnabas, himself a Levite, who was one of the first disciples in Jerusalem. He brought Saul – now Paul – with him and they remained there about a year. After that, Barnabas and Paul were sent by the Church of Antioch to spread the Gospel, first in Cyprus, and then in Asia Minor.

Towards the end of the third century Rome created a “super-province” called the “diocese of the East,” with Antioch as its capital. Thus, when the principal local Churches were recognized at the First Council of Nicaea (ad 325), “Antioch and all the East” was placed third in rank, after Rome and Alexandria.

1ST -3RD CENTURIES – MARTYRS AND ASCETICS

While St Stephen the Deacon, killed in Jerusalem, is recognized as the Church’s first Martyr, its first woman-martyr was St Takla. Converted by St Paul in Iconium, Asia Minor, she lived for many years in Syria’s Isaurian Mountains. She was killed by pagan sorcerers, jealous of her influence over the local population.

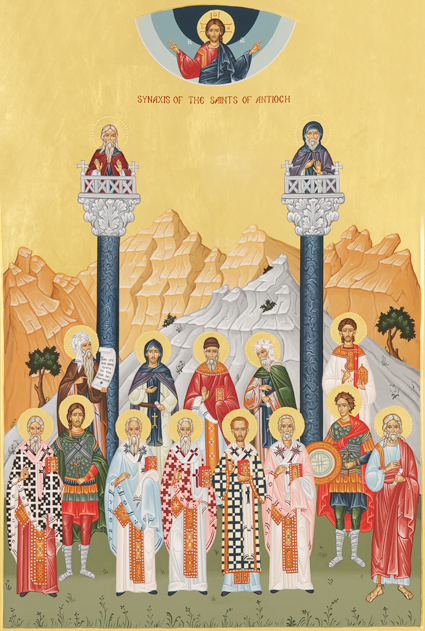

The Church of Antioch numbers many martyrs from the official persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Among them its early bishops, Evodios (who died c. AD 68) and St Ignatius of Antioch, called “Theophoros” (the God-bearer), taken to Rome and martyred c. AD 107. Other much-revered martyrs of the age are Saints Lucian, a second century priest and catechist, Babylas, its third-century bishop, and the martyred soldiers Sergius and Bacchos.

Syria was one of the first areas in which asceticism began to thrive. A group of virgins settled near St Takla’s dwelling after her death. It still exists as the Monastery of St Takla, near Maaloula, Syria. Another historic monastery still in existence is the nearby Mar Sarkis (St. Sergios) Monastery. Built in the fourth century on the remains of a pagan temple, it is one of the oldest monasteries in the Christian world. It is thought to have been built prior to the First Council of Nicea (ad 325) because it has a round (originally pagan) altar, a practice prohibited at that Council.

Antioch’s most famous ascetics were its fifth-century Stylites, Symeon and his disciples who spent their lives on platforms built on columns in a deserted area near today’s Aleppo. Devotees –even including legates of the Byzantine emperors Theodosius II and Leo I – consulted Symeon from a ladder placed against the column. Ruins of the column and the church built around it remain today.

4TH-6TH CENTURIES – COUNCILS AND DISPUTES

Syria was also a center of the theological controversies with the Arians over the divinity of Christ, with the Monophysites, over how He could be both God and man and with the Monotheletes, over how He could be perfect man if He had no human will – all of which led to the early Ecumenical Councils. A lasting division in the Church arose between those who accepted the fifth century Council of Chalcedon and those who did not.

This council based its decisions on Greek philosophical expressions which differed from the terminology used previously, notably by St Cyril of Alexandria. This caused the non-Greek communities in the East – Armenians, Copts, and the Syriac-speaking part of the Antiochian Church – to reject this council. The patriarchates of Alexandria and Antioch were divided into Chalcedonian Greek (Melkite) and non-Greek Churches. These non-Chalcedonian Churches are today called “Oriental Orthodox”.

Thus by the seventh century Christians of the Middle East were divided into “Roum” (Romans, i.e. Greeks), Jacobites (Copts and non-Chalcedonian Syrians), and Nestorians (the Church of the East).

7TH -13TH CENTURIES – OCCUPATION & EXILE

The weakened Chalcedonian or Greek patriarchate of Antioch was diminished further in succeeding centuries. The Arab conquerors saw the Greek Christians as allies of their enemies, the Byzantine Empire. They were persecuted more for being Romans that for being Christians. Many fled to places like Cyprus and Sicily.

During this time there was often no patriarch or one living outside the area. The Empire recaptured Antioch in 969 and provided the Church with 115 years of security and peace. This was shattered in 1085 when the Seljuk Turks conquered the area, soon followed by western Crusaders.

In 1098, Crusaders took the city, and set up a Latin kingdom with a Latin patriarchate. The Greek patriarchate continued in exile in Constantinople. During the nearly two centuries of Crusader rule, the Greek patriarchs of Antioch in exile gradually adopted their hosts’ Byzantine rite in place of their own Antiochian usage. Finally, in 1268, Egyptian Mamelukes seized Antioch from the Latins and the Greek patriarch was able to return to the region. By this point, a series of earthquakes and economic changes had reduced the importance of Antioch and the patriarchs relocated their headquarters to Damascus, the new capital of Syria.

1 comments