Source: Eparchy of Newton

Why do we have deacons in the Church? The emergence of this order came about in response to a specific issue which the apostles faced in Jerusalem. In Acts 6:1 we read that the “Hellenists” were complaining against the “Hebrews” “because their widows were neglected in the daily distribution.”

Almost from its beginning it seems the followers of Christ concerned themselves with feeding their poor. In first century society women who had outlived their breadwinner husbands were especially vulnerable, particularly if they had no sons to care for them. Needless to say, they had nothing like today’s workplace where they could be employed.

In Jerusalem the synagogues tried to ease the hardships faced by these women. Early on Friday men from the synagogues would canvass the city for goods and money for the widows. These would be distributed that afternoon, before the onset of the Sabbath. The Jewish believers in Jesus would naturally do something similar.

These first followers of the Lord lived with the memory of His preaching, His miracles, His death and resurrection and the descent of His Spirit fresh in their minds. Yet, human weakness made itself felt as well. The local believers – the Aramaic-speaking Jews of the Holy Land, whom Acts calls the Hebrews – seemed to be more attentive to their poor while neglecting the “Greeks,” those Hellenized Jews more inclined to embrace Greek culture, perhaps from places like Antioch or Caesarea, who had come to Jerusalem seeking help. Wanting to address this problem without allowing it to distract them from their proper task of preaching the Gospel, the apostles instituted the order of deacon to deal with the matter.

THE FIRST DEACONS

Acts identifies the first seven deacons and describes how they began their ministry. They were chosen by “the whole multitude” (v. 5) and presented to the apostles who prayed and laid hands on them. Prayer and the laying-on of hands has been the rite prescribed for the ordination of deacons, priests and bishops ever since.

Each of the seven listed in Acts bore Greek names. They may have been Hellenized Jews, the very people who felt as a disadvantage in the Jerusalem community. One, Nicholas, is identified as “a proselyte from Antioch” (v. 5) and would have been of pagan origin. The only two who appear elsewhere in Acts are Stephen and Philip.

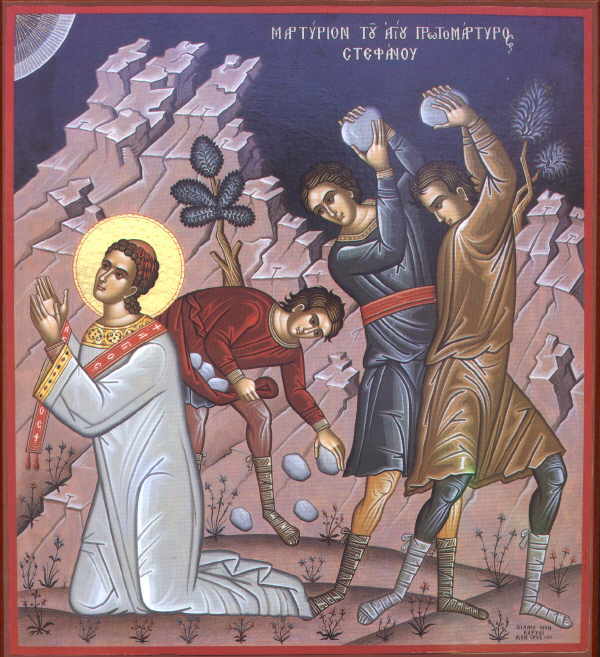

Stephen, described as “full of grace and power” (Acts 6:8), incurred the resentment of some Jews with whom he disputed. They denounced him to the Sanhedrin where he was condemned to death and executed (Acts 7). The Church honors him as the Protomartyr, the first to die because of his faith in Christ. Chapter 8 of Acts tells of the activities of the deacon Philip who preached the Gospel in Samaria and converted an Ethiopian on the road to Gaza.

Various local traditions connect Prochoros with Nicomedia, Nicanor with Cyprus, Timon with Bosra, and Parmenas with Macedonia. According to St Irenaeus, the name of Nicholas was connected with the Nicolaitians, a sect condemned in the Book of Revelation. It is not known whether he was actually a part of this group or, as Clement of Alexandria believed, they corrupted his teachings.

DEACONS IN THE EARLY CHURCH

The importance which deacons assumed in the first-century Church is shown in 1 Tim 3:8-13 where the qualifications for deacons closely resemble the requirements for bishops, with this exception. Potential bishops should demonstrate hospitality (as the head of a family) and an ability to teach (see 1 Tim 3:2).

From the first the role of deacons has been connected with a developing range of administrative responsibilities, beginning with the distribution of goods to the poor. During the Roman persecutions they ministered to prisoners. The third-century Martyrdom of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, tells how deacons served as intermediaries with the authorities to improve the condition of the prisoners and to communicate between the prisoners and their families. They arranged for the baptism of those who were catechumens and brought Holy Communion to the baptized, encouraging each one to remain strong in their witness to Christ.

As the Church developed, deacons were easily targeted during the persecutions. Their activities in tending to the needs of widows, orphans, the sick, and the imprisoned made them highly visible to the authorities. Since deacons were responsible for an increasing amount of sacred items such as liturgical books and vessels as well as funds for the needy, it was lucrative to seek them out and seize these treasures.

In AD 258 the Archdeacon of Rome, Lawrence was arrested and ordered to hand over the Church’s treasures. He gathered all the poor and the needy in his care and presented them to the Prefect, saying “Behold the treasures of the Church.” Lawrence was martyred and today is commemorated in the Church on the anniversary of his death, August 10. Other early deacon-martyrs remembered in our Church are Saints Benjamin the Persian (October 13), Vincent of Saragossa (November 11), and Habib of Edessa (November 15).

WERE THERE WOMEN DEACONS?

In Romans 16:1-2 we read, “I commend to you Phoebe our sister, who is a servant of the Church in Cenchrea that you may receive her in the Lord…” It is thought that Phoebe may have brought St Paul’s epistle to the Church at Rome. The Greek word translated here as “servant” is diakonos, giving rise to the idea that Phoebe was an ordained deacon. Both Clement of Alexandria and John

Chrysostom recognized Phoebe as a deacon and she is commemorated as such on September 3 with this troparion:

Enlightened by grace and taught the Faith by the chosen vessel of Christ, you were found worthy of the diaconate; and you carried Paul’s words to Rome. O Deaconess Phoebe, pray to Christ God that His Spirit may enlighten our souls!

There are a number of references over the next few centuries to women deacons, but their place in the Church is debated. Many say that they ministered to women, particularly catechumens, preparing them for and assisting in their baptism where the presence of men would have been unseemly. They were ordained in a rite similar to but not identical with that of deacons.

Perhaps the best known deaconess in the Byzantine Church was St Olympia (July 25) who headed a community of some 250 women. She is known for her care of St John Chrysostom, attending to his garments and preparing his meals, which she sent daily to the episcopate. Other leading deaconesses of her community known to us by name were the Pentadia, Procla, Sylvina, and Nicarete.

As Christianity became the norm in the Byzantine Empire the adult catechumenate – and the deaconesses’ principal function – came to an end. Deaconesses survived for a time only in women’s monasteries. They all but died out in the Armenian. Georgian and Greek Churches after World War I but have since been revived. Deaconesses in the Coptic Church are comparable to Catholic sisters. They are not ordained, but blessed.