by Brent Kostyniuk

It has become fashionable to resurrect historic injustices and blame them for present day conditions. However, there is one event which remains little known, which brought horrible sufferings to thousands, and for which no reparation has even been considered—the internment of Ukrainian Canadians during World War I.

Imprisoned

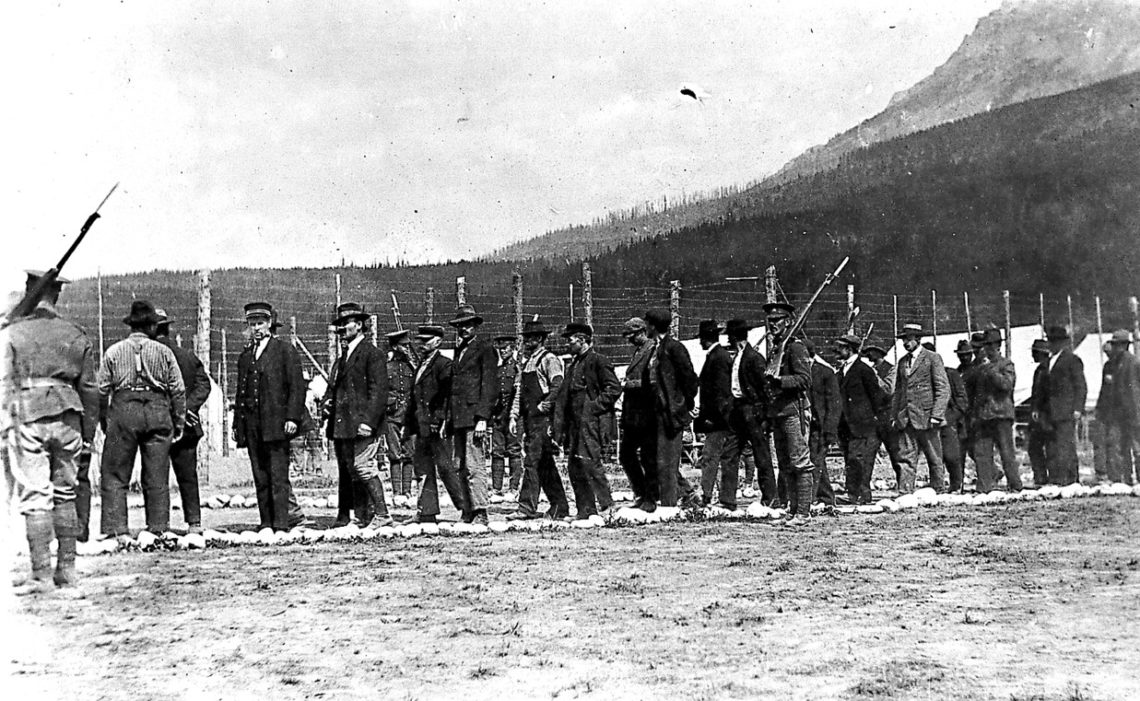

This infamous incident in Canadian history began when the War Measures Act came into law in 1914. Under the pretext of safeguarding the country from enemy aliens, some 8,500 men were interned as prisoners of war. Far from being enemy alien combatants, these men were civilians. Some detainees were foreign nationals, although others were British subjects or even Canadian citizens. The majority were pioneer settlers, mostly ethnic Ukrainians. It had already been 23 years since the first Ukrainian settlers had arrived in Canada. During that time, they had survived in the wilderness, creating farms to provide food for their families and for the rest of the country.

The internment camps were located in wilderness areas where the prisoners were forced to work on government projects contrary to the international convention which held (and still holds) that prisoners of war could not be forced to work on anything other than that which was required for their own welfare. In all, over 30 camps were created across Canada. One of those with the harshest conditions was Castle Mountain, near the endpoint of the unfinished Banff to Lake Louise road. Established on July 13, 1915, it was the largest camp in the Rockies, with several hundred prisoners at any one time. A total of 660 men were interned there during the course of the war. Conditions were harsh. Prisoners worked eight hours a day clearing and grubbing roadbeds with axes, picks, and wheelbarrows. However, the workday extended to up to 13 hours as prisoners were forced to march to and from the worksite. The backbreaking work was made even worse by the sometimes-brutal treatment of guards. Prisoners’ only rest came on Sundays, or when snow, cold, or rain made the work too difficult. Eventually, prisoners completed 10 kilometres of the Banff highway through to Lake Louise.

It Was a Prison

There was no mistaking the purpose of Castle Mountain. It was a prison camp, surrounded by two lines of barbed wire fences. Prisoners were sheltered in tents. However, these were so inadequate during the bitter cold and snow of winter, the camp was relocated to military barracks in Banff, near the Cave and Basin hot springs. While in Banff town, prisoners worked on several projects familiar to tourists today. These included clearing the buffalo paddocks, quarrying stone for the Banff Springs Hotel which was under construction at the time, reclaiming land for the golf course, and smaller projects such as sidewalk and street repair. With the warmer weather and melting snow of spring, prisoners would return to Castle Mountain. Much of what tourists enjoy today is the result of the forced labour imposed on the internees at Castle Mountain.

Aside from the hardships of weather, living conditions were far from pleasant. Each man was allowed 12 ounces of meat a day; however, this included bone and waste material. The actual edible amount was much less. What meat they did receive was often spoiled, as were the staple root vegetables included in the rations. Meals often froze before the prisoners were able to eat them. Men took to eating raw or smoked fat which could withstand the freezing temperatures.

Nothing remains of the Castle Mountain internment camp. Near the site, a statue and plaque have been placed along the original Banff to Lake Louise road on which the prisoners laboured.

The experience left the prisoners with a deep sense of shame. Although they had committed no crime, other than leaving their homeland to seek a new life at the behest of the Canadian government; they had been treated as criminals and were left with the sense that they were, indeed, criminals. They would not speak about their experience. Sometimes, even their own children grew up without knowledge of what had happened to their fathers.

Being Released

This tale has a very personal aspect. My own great grandfather, Yurko Kostyniuk, was interned at Castle Mountain. Camp records show he was “released” on July 8, 1916, to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. In reality, this was just another form of the forced labour which all of the prisoners faced. Unknown to him, his wife Anna passed away about this time, worn out from the almost impossible task of trying to raise seven children without a husband to help.

Within three years, Yurko would be interned at Castle Mountain, Anna would be dead,

and the children virtual orphans.

When Yurko eventually returned to his family and the homestead he had worked so hard to carve out of the prairie wilderness, he must have been a broken man. His internment was treated with shame and secrecy in the family. Although his children were aware he had been taken away, his grandchildren knew little or nothing of the internment; some remained convinced throughout their lives it had never happened. Sadly, Yurko lost the drive and pride which he must have had when he started his homestead. A dozen years after his release, he could no longer face life in Canada, the land he had hoped would bring freedom and prosperity for himself and his family. On his own, he returned to Ukraine. He died there, having replaced the suffering of life in Canada, with the suffering of the Holodomor and more.

Sometimes there is just no way to find a happy ending to a story. This is one of them.

Featured Image: New Arrivals going into Castle Mountain. Photo: Ukrainian Canadian Congress-Alberta Provincial Council.